Last month saw the publication of Savanta’s research into inclusive design in Smart Data schemes for the Department for Business and Trade (DBT).

The UK Government’s 2022 Digital Strategy identified ‘unlocking the power of data’ as a key pillar for the growth and resilience of the digital economy. Smart Data is an important part of this, as a framework for data sharing which aims to enable customers to realise the value of data about them. As such, this is a policy area which is likely to be important for several sectors across the UK economy in the near future.

Following the success of the first Smart Data scheme in the UK – Open Banking – DBT wishes to support the growth and acceleration of schemes across several industries of the UK economy. In support of the development of these schemes, Savanta has produced research to ensure that consumers with vulnerable characteristics are able to fully participate in schemes and share in their benefits.

The report, published here, builds upon existing literature on inclusive design and details twenty-one design principles to ensure that these consumers are able to fully engage with schemes and harness the value of their data.

How exactly does Smart Data unlock the value of data?

Most companies that we interact with on a day-to-day basis sit on large quantities of data about us. This is no secret. But it is striking, given the frequency with which this occurs, how often it feels that customers are not fully sharing in the benefits of this data being generated.

Customers can already request to access data about themselves, thanks to the ‘right to data portability’ under the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). But this data is often shared slowly, in an unwieldy format, and without the context needed for consumers to actually get full value from it. For example, I can ask to see the data that my energy provider holds about me, but the file I receive is not likely to be one that I can readily use to work out if I am on the best possible tariff for my circumstances and preferences.

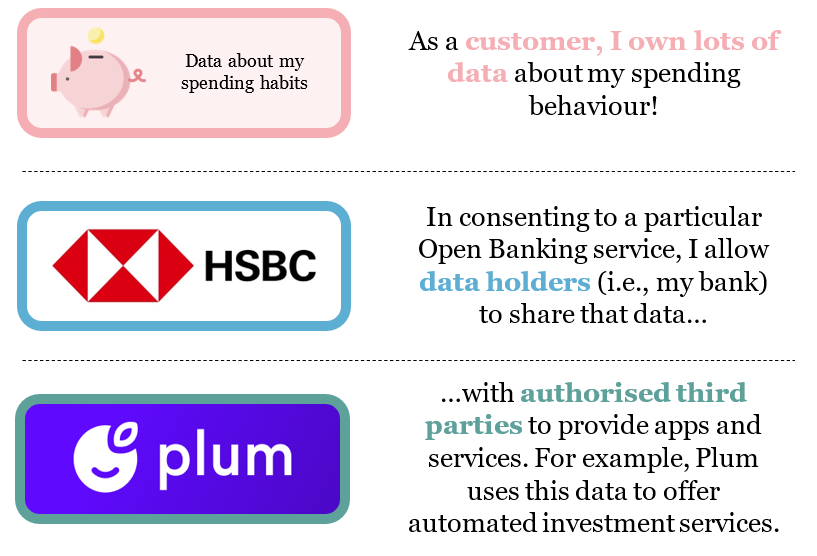

Smart Data schemes build upon this right to data portability to make it easier for customers and small businesses to use data held about them. Smart Data is not a type of data, but a set of schemes providing the infrastructure for the fast, secure sharing of data in useable formats. At the request of customers, data holders must share their data with authorised third parties in a format that allows those third parties to offer services which save consumers time, money and effort. In the context of the energy industry, for instance, I might ask my energy provider to share my consumption behaviour with a third party that can advise me on whether I could be getting a better deal elsewhere.

Many such services are already operating within the UK, as part of Open Banking, the only active Smart Data scheme in the UK at present. Customers ask banks to share their data with authorised third parties in order to receive, for instance, automated investment services and budgeting tools which are tailored to their needs and bring tangible benefits. The diagram below shows how a particular service in Open Banking works, and applies in more general terms to all services offered as part of Smart Data schemes.

7 million consumers and SMEs are actively using Open Banking services as of January 2023, with the annual potential benefits estimated to be £12 billion for consumers and £6 billion for businesses. Given the success of Open Banking so far, DBT are looking to support the growth and acceleration of potential new schemes such as Open Finance, Open Communications, and a Smart Data energy scheme.

As the cost of living continues to increase, there is an obvious benefit to supporting the development of services that can save consumers time, effort and money. But there is also a wider economic case for the rollout of further Smart Data schemes – unlocking the power of customer data is also a measure that could feasibly increase competition and encourage innovation across sectors of the UK economy.

Why is inclusivity important in Smart Data schemes?

The May 2022 instalment of the Financial Conduct Authority’s Financial Lives survey found that nearly half of UK adults (47%) showed one or more characteristics of vulnerability, namely: poor health such as cognitive impairment, life events such as new caring responsibilities, low resilience to cope with financial or emotional shocks, and low capability such as poor literacy or numeracy skills.

Despite any potential benefits of Smart Data schemes, there is recognition that consumers with these vulnerable characteristics will interact differently with them. Unless schemes are designed with the consumers’ specific needs in mind, they may be exposed to unfair practices, may not receive the appropriate level of protection from fraud or scams, or may find that there is not appropriate support mechanisms when things go wrong. Schemes must therefore be designed inclusively to make sure that these potential consumers harms are prevented, and to ensure that all consumers are able to harness the value of their data.

This is where the research conducted by Savanta comes in: we were commissioned to further the Department’s understanding of the characteristics are most likely to lead to consumers being excluded from schemes, the specific barriers that they face, and the scheme design principles which would best mitigate these barriers.

How can we ensure vulnerable consumers are able to fully participate in Smart Data schemes?

There is plenty of existing literature on the topic of vulnerability and Smart Data schemes in the UK and abroad, but much of it is too abstract to be straightforwardly implementable by scheme designers. It discusses some of the main barriers to inclusivity, in quite general terms, but offers little in the way of tangible solutions.

Savanta therefore furthered this existing research by retaining the broad barriers to inclusivity uncovered by an initial review of this literature, then conducted targeted primary research to address the gaps and ambiguities, and to understand what addressing each of these barriers might look like in practice.

Four main barriers were identified, which were recontextualised as four ideal outcomes which, if realised, would amount to vulnerable consumers being able to participate fully in schemes. The diagram below shows these four pillars.

Through the primary research, Savanta then identified twenty-one more specific design principles which, if implemented, would go some way to ensuring these outcomes can be achieved. The primary research took the form of a half-day workshop and qualitative interviews with senior stakeholders representing consumer advocacy groups, customer data holders, and third-party organisations which would use the data to offer services as part of schemes.

The report details and contextualises each of the twenty-one principles in turn. Rather than attempting to summarise all twenty-one here, I’ll use the second principle as an example. This principle aims to support the pillar of ‘trust’:

Existing literature notes that consumers with lower levels of digital and financial literacy find it harder to assess the legitimacy of a scheme, app or website. Primary research participants concurred, and suggested that this uncertainty may lead to consumers with these particular vulnerable characteristics being unwilling to sign up for schemes at all. If these consumers do not feel comfortable participating in schemes at all, it cannot be said that schemes are designed with their needs in mind.

So, the research sought to advance upon merely stating the issue, and drew upon how this barrier is addressed outside of the context of Smart Data, to provide a tangible way to mitigate this difficulty. It found that consumers in these circumstances often utilise the support and advice of trusted individuals, particularly when it comes to financial decisions. As such, taking steps to design signup mechanisms such that it is easy to involve these trusted contacts is a measure that is likely to address this difficulty in many cases.

Cumulatively, these twenty-one principles address many of the obstacles to those four ideal outcomes. They are not exhaustive, and directly testing many of these measures with vulnerable consumers is an important next step as the Department looks to explore the research findings – but they amount to clear, tangible ways to promote inclusivity in a policy area which is likely to have a large impact on several industries over the next few years.

Note: These principles represent the results from research findings and does not necessarily represent government policy. Similarly, this blog does not represent government policy and the views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department for Business and Trade.