In 1957, Ford introduced a revolutionary new car, the Edsel. The development of the Edsel began in 1955 with one of the most extensive R&D efforts in the history of auto making. This included far-reaching market research to determine the most preferred features and functions to include in the car. Edsel offered several innovative features, among which were its “rolling dome” speedometer, warning lights, push-button Teletouch transmission shifting system in the center of the steering wheel, ergonomically designed controls for the driver and self-adjusting brakes.

Despite all of Ford’s research, innovation and promotional efforts, the Edsel was a dismal failure; so much so that even today, the name Edsel synonymous with failure. So, what happened?

Among other things, one reason for Edsel’s flop was the inappropriate use of market research. Consumers were asked to evaluate many product features and attributes in isolation. They were asked to choose their favorite body shape, grill, fenders, wheels, interior features, engine, and colors, all individually, and not with the whole product in mind. Ford took the “winning” feature in each category and put them together to produce the Edsel. This resulted in a final product that some have called the duckbilled platypus of the automotive world.

This mismatching of features could have been avoided by using a technique called Discrete Choice Analysis (DCA). DCA is an analytical technique used to simulate real-world consumer purchasing behavior. Through an experimental design, consumers are simply provided with a series of product choices, varying by particular attributes and levels. For each choice set, consumers are asked to choose the one bundle of attributes that they would most likely buy or none of the choices. The decision that the respondent makes is designed to mimic the real-world market. However, the respondent is not consciously aware that they are being measured on the relative importance of each product attribute.

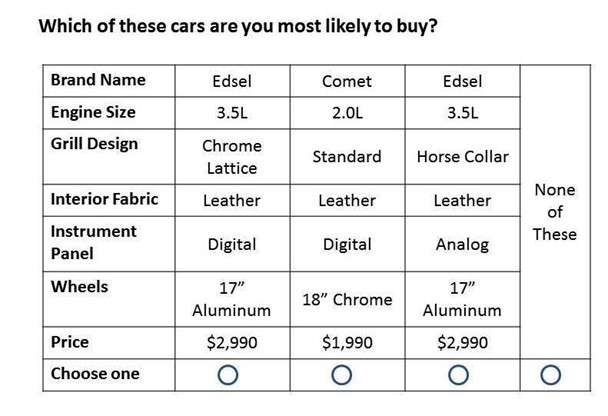

For example, if we were going to attempt to design a new “Edsel”, we may want to include a number of attributes in the test including; Brand Name, Engine Size, Grill Design, Interior Fabric, Instrument Panel, Wheels, and Price. Each attribute can then be broken down into a number of levels. For instance, levels for engine size may be 2.0L, 3.0L, or 3.5L. A sample choice set is shown below:

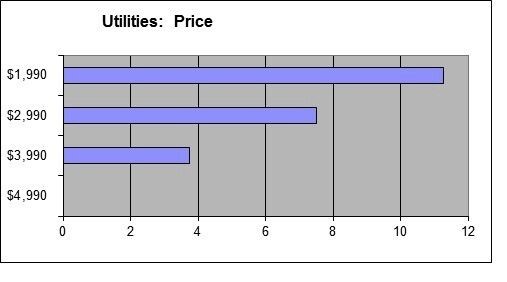

DCA provides three main outputs that marketers can use in the product development process. First, by looking at the individual utilities or preferences of each of the product attributes, you can determine which attribute has the greatest impact on consumer choice and the relative impact of that attribute. In our example, the car’s price accounts for 54% of the consumer choice, followed by engine size.

Second, within each attribute, you can see the relative preference of each attribute level. In the example below, a product with a price of $1,990 is preferred 1.5 times more than one with a price of $2,990.

Finally, we provide an Excel-based simulator that can show the forecasted share of market for any combination of attributes and levels to determine the optimal combination of attributes for a potential product. We will demonstrate how the simulator can be applied in Part 2 of this blog post.

If used, would Discrete Choice Analysis guided Ford to a better result with the Edsel? I guess we’ll never know for sure. But, we can certainly provide clear, actionable, and timely information for future product developers through this market research tool.

Read Part II: How A Discrete Choice Simulator Can Be Used To Launch the Right Product (Part 2)