If a week is a long time in politics, a year can feel like a lifetime. Liz Truss was appointed Prime Minister a year ago today, having defeated Rishi Sunak in the first of two Conservative leadership contests in 2022, replacing Boris Johnson following his resignation after a tumultuous year that started with the Partygate scandal. While Johnson, in many respects, got the ball rolling for a Conservative defeat at the next election, Truss, in her short, 49-day tenure, threw said ball off a cliff. She left her party, and her successor, with a seemingly impossible mountain to climb to restore any sort of credibility to the government’s polling numbers if they are to avoid a humiliating defeat at the next general election, reversing the comfortable majority won in 2019.

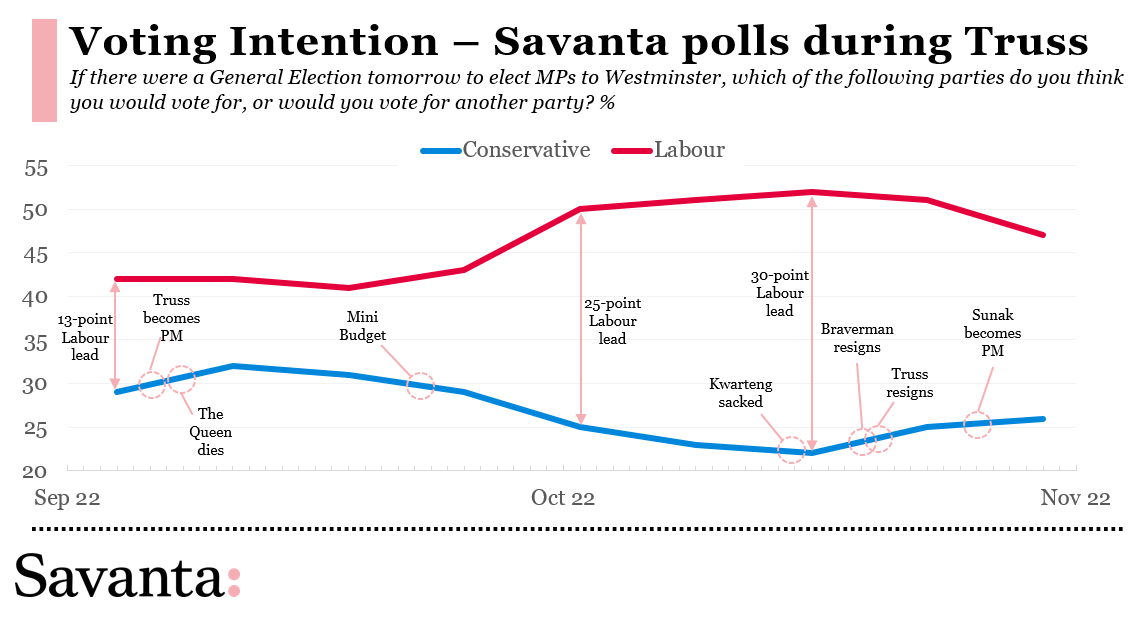

Truss entered office with Labour leading the Conservatives by 13 points. Much of this was down to Johnson, with the Labour lead slowly building throughout 2022 due, in most part, to the ongoing saga of Partygate. Whether Truss would get a ‘honeymoon’ was debated by commentators: most new Prime Minister’s, whether they enter Downing Street off the back of an election victory or not, usually ride a wave of positivity and public goodwill for at least a few weeks before the real nitty gritty of governing takes hold. Truss’ honeymoon never came, though. On the third day she was Prime Minister, Her Majesty the Queen died. Savanta, and other pollsters, continued collecting data, but the cut-and-thrust of politics, which had only recently returned after a summer recess and a Conservative leadership contest, was put on hold for another fortnight. During this period of national mourning, the Conservatives’ deficit reduced to 10 points, but this never felt like it was a ‘new Prime Minister’ bounce, as the public’s minds were simply elsewhere. Any honeymoon for Truss would need to come almost three weeks in the job.

Except the pressure, by that point, to get on with the job, had risen. Truss was never afforded any time to bed in or ride the wave of goodwill often afforded to new PMs. Four days after the Queen’s funeral, Truss’ Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, gave a mini-budget statement to the House of Commons, timed deliberately to detract from the start of Labour party conference. Setting out so-called ‘Trussonomics’, the mini-budget, free from OBR scrutiny, outlined a reworking of the economy away from what Truss believed was the economic establishment. The statement included reversing the planned national insurance and corporation tax rises, along with scrapping the cap on bankers’ bonuses and, most controversially, the top rate of income tax. Over that weekend, Labour’s lead in Savanta’s polling rebounded to the low teens.

The week that followed was a disaster. With financial markets on alert as the pound fell after the statement, Kwarteng followed up the mini-budget by stating there were to be more economic changes to come, promoting a run on the pound, a pensions crisis, fears of much higher borrowing and an unprecedented Bank of England intervention. In aiming to deliver what she believed was a set of staunchly Conservative economic policies, by putting interest rates and pension pots at risk, Truss had alienated a vast swathe of would-be Tory voters. A series of car-crash BBC local radio interviews followed, and by the start of Conservative conference the following week, Labour’s lead had jumped from 14 points, to 25.

Subsequent weekends and a few economic u-turns later, Savanta showed Labour leads of 28 points and 30 points – some pollsters showed leads as high as 39 points. These numbers were not just Labour majority territory, or even Labour landslide territory; these indicated an absolute Conservative wipeout where, if replicated out at a General Election, they’d have fewer MPs than the Liberal Democrats. Truss sacked her Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, in the period between Savanta’s 28 and 30 points Labour leads, but allowing Kwarteng to eventually take the fall for the mini-budget did little to draw attention away from Truss. In the space of a few weeks after the Queen had died, polling indicated Liz Truss had taken the Conservative Party from potentially depriving Labour of an outright majority at the next election, to the precipice of political irrelevance.

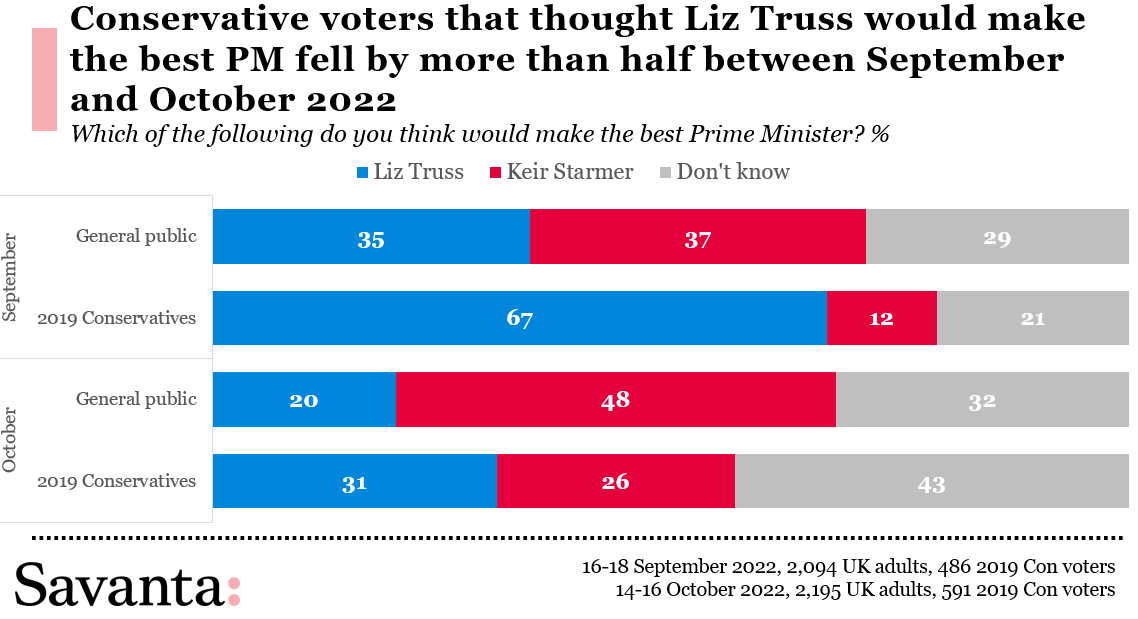

Conservative voters told pollsters that they were deserting the party en masse. Savanta’s final poll of Truss’ tenure showed 25% of Conservative 2019 voters switching directly to Labour; the figure for her first poll was 12%. She began with a net favourability rating of +41 among Conservative 2019 voters; it ended on -30. At the beginning of her premiership, 67% of 2019 Conservative voters thought she’d make the best Prime Minister compared with Keir Starmer; by mid-October, just 31% felt the same.

More than half (57%) of the public told us that they ‘dislike both Liz Truss and her policies’. Among 2019 Conservatives, a quarter (24%) said that they disliked ‘both Liz Truss and her party’, while a further third (33%) said that they ‘dislike Liz Truss but like the Conservative Party’. Just 24% of Tory voters liked both their leader and the party. Her resignation became an inevitability.

After his own resignation, Boris Johnson’s favourability rose. In fact, tracking his net favourability over time, Johnson has two noticeable troughs: his first apology to the House of Commons for attending a Downing Street garden party, and his resignation following Partygate and the Chris Pincher scandal. In subsequent months, his ratings rose, not ever back to pre-Partygate levels, but enough to indicate a change in public sentiment. There are a few theories for this: some, at a more extreme end of the spectrum, believe it’s evidence that the public have forgiven him, and he’d be a political asset to the Conservative Party again; the one I personally ascribe to is that Johnson is ‘out of sight, out of mind’ to the average voter, and this lack of attention creates an indifference that would quickly sour were he to become a prominent political figure again.

But maybe ‘out of sight, out of mind’ is unique for Boris Johnson. The distaste voters show towards him is more personality-based, rather than Truss’, which is more economic. The public are still feeling the pinch of her policies, whereas Johnson’s misdemeanors are perhaps easier to forget, if not forgive. Following her resignation, Truss’ ratings have never recovered. A net favourability rating of -49 as she left office, is -54 today. It’s -52 among Conservative 2019 voters, and even -36 among current Conservative voters; for context, among current Tories, Sunak’s rating is +66 and Boris Johnson’s is +39. Keir Starmer’s rating among current Conservative voters is just eight points lower than that of their former leader.

These numbers, unlike anything I’ve seen in my career, put the Conservative Party on the backfoot to such an extent they’ve struggled to recover. Come Rishi Sunak’s anniversary in office we can examine in more depth how, at the time of writing, he’s failed to restore much credibility to the Conservative Party. But his task was made exponentially more difficult following the short leadership of his predecessor, who inherited a salvageable polling deficit and turned it into one that needed a miracle.

For further information and insights on politics, please get in touch. And for more information on Savanta’s approach to political research click here.